By Fanny Revault

Fascinated by nature since his early childhood spent in Morocco, Manal Rachdi has always strived to study and understand it, as well as the ancient architecture he observed in his youth. Later, he would strive to synthesize both passions: nature and culture. In his work, plants have plenty of room to grow and are seamlessly integrated to the organic and rigorously-shaped masterful structures. Beauty, poetry, and space-sharing go along with environmental and ecological considerations. Manal Rachdi’s architecture allows for a soothing way of life.

How did you end up being so passionate about architecture?

I have always been fascinated by the architecture around me. I lived in a centuries-old country in which ancient architecture is incredibly well conceived, and I was struck, very early, by its details and overall quality. But I was also fascinated by nature.

When I was 16 architecture was one of the occupations I was drawn to. I come from a family of scientists, with doctors and engineers, and my parents did not understand this choice; they pushed me towards dental pharmacology. That led me to study biology and geology, to the study of the infinitely small and the infinitely large. Actually, I find architecture to be the synthesis of the two. The infinitely small reflects the functioning of the world, and the infinitely large refers to the environment, to ecology, to everything that surrounds us. In my architectural work I try to synthesize the infinitely large and the infinitely small.

What are the essential principles that govern your architectural work?

For me there are two things that are important, almost necessary, when one creates a work of architecture: the poetry of cities and the beauty one can bring to them. Architecture can become a repository of places in which people live, work, and reside differently around the medium of nature. I use nature not as ornament but as an element that brings rigor, protection, and refreshment to architecture. These are different kinds of places to live, new places inside the architecture itself, on the roof, on terraces, in common areas, as in the structure we conceived for Pixel where there are big patios that both allow for the setting of these pieces of nature and provide common living areas, or on the roof of the project at Lille Cascade, which is a succession of gardens that are connected to each other, that allow the people who work there to work outside and to make use of the outside spaces. So I like to conceive living areas, common areas, areas that allow for shared moments for their inhabitants.

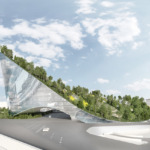

FLOWING PARK – Moscou, Russie

FLOWING PARK – Moscou, Russie © Manal Rachdi Oxo Architectes

LE CRISTAL – Nanterre, France

LE ROCHER – Nanterre, France

PIXEL – Tours, France

PIXEL – Tours, France © Manal Rachdi Oxo Architectes

KASKADE – Lille, France

Would it be accurate to say that nature is at the heart of your architectural work?

Yes, in my work I try to establish a link between architecture and nature. I imagine spaces in constant contact with nature, and that is the architecture I am passionate about. It is an architecture that blends into nature, that becomes like an inhabited mountain, as we did in the project Ecotone. These spaces become a moment in which architecture and nature become completely integrated and connected, and create areas where people feel good.

One has the impression of being within a natural area that would have been brought back into town or that could have been integrated into a dense, urban network. The freshness that nature can bring, that is what I am seeking in my architecture, that can provide natural havens in the city.

ECOTONE – Sophia-Antipolis, Antibes, France – © Manal Rachdi Oxo Architectes

ECOTONE – Sophia-Antipolis, Antibes, France –

MILLE ARBRES – Paris, France –

You were talking about studying the infinitely large and the infinitely small… Do you draw your inspiration from nature itself?

In my work, being inspired by nature is also an aspect of the reflection on biomimetics. Projects like L’Arbre Blanc (”The White Tree”) are examples of it. We draw our inspiration from a tree to create a specific architecture that is unique because it is developed in an environment, in a place, in a setting that is extremely favorable.

There is also the project Art’Chipel. It is a housing project entirely surrounded by nature which uses the camouflage strategies of the chameleon. The reflection of nature onto the architecture connects it directly to nature. And when you are inside the architecture, protected by this reflective shell, you constantly see nature at every instant from within your house. So this constant link between inside and outside, the constant visual sliding between the two, always having the natural environment around you. It is an aspect that I find vital in architecture in order to live well.

ARBRE BLANC – Montpellier, France

ART’CHIPEL – Marseille, France © Manal Rachdi Oxo Architectes

ART’CHIPEL – Marseille, France © Manal Rachdi Oxo Architectes

ART’CHIPEL – Marseille, France © Manal Rachdi Oxo Architectes

At a time when the environmental movement occupies a central place, how do you integrate architecture and decarbonization?

I always consider biodiversity and nature in my projects: there is a balance to find between what exists and the way in which one integrates architecture within an environment. Nature sometimes covers the architecture, sometimes becomes integrated into it, sometimes supports it from underneath.

So yes, there is a will to create an ecological, environmentally friendly architecture that uses less energy. Thanks to its morphology it becomes an architecture that does not need air conditioning because it is naturally ventilated, no need for technological help. It is a natural morphology that allows one to live in the South.

CALABRE © Manal Rachdi Oxo Architectes – Philippe Rizotti, Samuel Nageotte, Tanguy Vermet

ART-CHIPEL

Nature is predominant in your work. What are your thoughts on the concept of the Smart City and its uses of new technologies?

There is a lot of talking about the Smart City… I think that at any given time, cities are the smartest of their time. There is no Damned City, that does not exist. Technologies allow us to evolve bit by bit, but that does not mean that one should forget the very essence of architecture, of biodiversity, of what allows us to live. I plant a lot of trees in all my projects.

Why do we plant trees? Very simply because it is a way to refresh, but also to produce oxygen and to absorb CO2. It is also a way to enliven our visual environment because we are designed to live in nature. And I am always vigilant because technology, no matter how incredible it might be, should not draw us further away from reality and from what our being is, that is, linked to nature. It needs to be at the service of preserving biodiversity, and ecological and environmentally friendly architecture.

Once it is built, the architectural work has a life of its own. Environment, nature, and the passage of time free it from the ties with its designer. How do you integrate this aspect?

Nature allows architecture to evolve in time. I find it absolutely fascinating to not be able to control the final result and to see the architecture constantly evolve. Architecture moves, transforms, retransforms itself — it has several lives within ils life… We tried to create architectural works that can be integrated into a multitude of programs. It is fascinating to think that architecture can evolve. It is a construction site. And nature is a permanent construction site…

What feelings would you like the people who live in your architectural works to experience?

There is a feeling that I would like to share and that I always try to transmit to the people who live or go through my buildings, it is a feeling of lightness, of beauty, of light, this feeling you experience when going through a forest, feeling light and peaceful. If I manage to do that one day, or every time, I will be the happiest of men, the most accomplished of architects. Architecture is not a demonstration of existence, or of strength. For me, architecture is an act of disappearance. When you feel good in a place, it is because the architecture has succeeded in transmitting what is needed.

October 2023