By Fanny Revault

Jacques Villeglé, a major visual artist, designed in 1949, through the almost exclusive appropriation of the lacerated poster, a singular and prolific work. Walking the streets of Paris, the artist lets his gaze wander over the posters, waiting to be caught by the one who will resonate with a certain harmony. The artist reveals by her cutting, a poetry hidden in the heterogeneous thickness of lacerated papers, offering tables where typography then colors and illustrations intermingle. At the crossroads of New Realism and Lettrism, his work, anchored in current events, is admired by the young generations of urban art. Meeting with the artist in his Parisian workshop where he gives us a striking testimony on the artistic life of the second world war until today …

When did you become interested in art during the war when access to books was rare?

Well, this is an historic date, but it was June 6, 1943, a year before the landing during the occupation. During the occupation, there was complete censorship of contemporary art. Picasso, I knew the name of this gentleman who painted an eye in place of the navel, and therefore this June 6, I returned to the oldest bookstore in the city, which was called Lafolye-Lamarzelle in Vannes, very old publishers . And I pick up a book from the floor at the back of the shop where he had all the unsold books. At that time, publishers didn’t have a lot of paper, so they took unsold products out of the attics in bookstores; and I pick up this book by Maurice Raynal on contemporary painting from 1906 to the present day, dated 1927; so, I’m going to have the information before my birth.

What made you decide to join the art world?

I did my secondary education with Jesuits, and I was always last in class.

It was the largest Jesuit middle school in France, six hundred students! Culturally, there was nothing about modernity. I couldn’t get used to that education, and when I came across this book, it was a complete reversal. The only thing that was incomprehensible to me was a reproduction and a sentence by Joan Miró: “I want to assassinate painting”; it was incomprehensible to me … So that asked me questions, but instead of being put off, I said “I want to know this environment, I want to enter this environment”.

Why did you choose the posters on the city walls?

In cubism, I saw that typography counted and replaced the naked woman; the typographic character in the painter returns to Braque and Picasso stole from him. That’s what led me to the posters. On top of that, I had a brother who was very sick and my parents subscribed him to ABC school whose motto was “If you can write, you can draw”; so Braque’s characters in cubist painting and this sentence ‘if you can write, you can draw’ naturally oriented my interest in writing.

Through your work on typography, you feel a filiation with the Cubists, establishing another relationship to the work …

Posters, at the beginning had no illustrations, there were only characters. So, you see, I was a successor to cubism that had introduced the characters in the painting. But I saw the danger, because the young painters said to me “you are always in the posters” as if I were saying to them “you are still doing oil painting”! So, I started to make a thematic catalog, in general, the artists make a chronological catalog, and I saw that I had very different themes, that I therefore obeyed reality, but this reality I chose it, it was the choice that was important.

How did you choose the poster?

It was by looking carefully that I saw the evolution; what I was looking for was a poster that would change the atmosphere. My quality is that I have a sense of proportion; I did architecture and architecture, it’s the proportion that counts to make a great achievement.

After studying at the Beaux-Arts in Rennes and then Nantes, you arrive in Paris and walk the streets of this city. What is the post-war Parisian atmosphere and your first encounters in the art world?

There was a movement of great freedom with liberation. The first artist I really knew was Camille Bryen, when I met him, he was very poor and despised; in Paris, Camille Bryen, therefore Wols were a movement, informal Art, because what was strongest in painting was geometric painting; Mondrian, Malevitch … I come out of the Jesuits and these are painters who lived through communism, the revolution, so that made that I’ve never been interested in politics.

How did you defend your art at a time when abstraction dominated?

Apart from abstraction, there was no future … and I was looking for something with typography, which is not abstract, it is writing. For example, the color, you never had a beautiful blue, it was always a little gray. Paper manufacturers and chromologists were studying and developing this color; gray has turned blue gray, instead of yellow gray. So, I saw that there was an evolution in the color. During the occupation, I came across a book on the poster, so I knew that the poster was evolving, and the concern of artists is to evolve; so, they have to work so that their paint doesn’t look like the paint from the previous year. I knew the tear in the street poster was going to change and I just had to choose.

What triggering act let you impose yourself on the artistic scene?

This is the 1959 biennial made by a conservative who pulled us out because the press fell on us and it was a success. At that time, there was a certain Pierre Restany who came from Morocco, and who was very young, nineteen, twenty years old and who had a somewhat strict ambition.

You claim the collective gesture to the individual gesture, which made emerge the notion of the “anonymous lacerated” …

Yes, because the poster is the street, there is not my layout, and it is the tear which was made by an anonymous, I spoke of the “anonymous lacerated”, I should have said of an “anonymous lacerator” but “lacerated” it was lighter because a lacerator, according to the dialectic, is a lacerated being.

Affirming that “The life of an artist must start with strolling”, you become surreal …

The surrealists, I frequented them, but I only had friendly relations with them. I met André Breton and I was friends with François Dufrêne who was one of the youngest letter makers… Man Ray attended our exhibitions at the J gallery of New Realists; intimidated, he was against a wall, and people did not know him; and I said ‘but it’s Man Ray, a very great photographer’ so we said ‘you, with your story, and Man Ray, it was maybe three, four years before his death that he was recognized and that he had good exhibitions in a museum.

What knowledge of Dadaism did you have at the time?

Dadaism was very disdained at that time; we did not know it so to speak… The sentence which was known to Dadaism was “it is Dadaism which prepared the way for surrealism”; it’s André Breton who comes back from America, all the newspapers talk about him, and it was not in his temperament, he preferred to have a hidden life.

” I do not search, I find “. This Picasso phrase embodies your approach …

An artist is the unexpected, he will reveal something to you, that another finds indifferent. The phrase ‘I do not search, I find’ means that if one finds, it is that one is unconsciously searching. So, the artist likes spontaneity, he would like to surprise himself.

You have often been brought closer to the ready made by your appropriation of reality … What distinguishes you from Duchamp in your relation to the object?

The ready made is an object of provocation, lacerated posters, provocation is in the discourse. But if I had had a more classic speech, which does not seek the difference, I could have succeeded better. “The anonymous lacerate” shocked many people. You see, Marcel Duchamps, he plays the indifferent, so what I like is that it is by his indifference that he is very well known, and if he did not seem indifferent, he would be an artist like all the others…

Since you debuted, you quote André Breton saying that “an artist must live in the shadow of his work”. Why this desire to fade behind his work ?

You see, this is common to all artists… Leonardo da Vinci wrote in reverse, for example, because artists do not like us to know how they work, and in our time, with gestures, we saw Mathieu painting in public, he said it was instinct, but it was not true. So, we try to surpass himself, the artist would like to surprise himself with what he is doing. An artist, he can make a masterpiece, he knows that he obeyed the order number, or that he destroyed it, etc…

What do you want to express?

Art is made to disturb; it is not made to be constantly propaganda. The lacerated poster is against advertising. Propaganda is ideas, advertising is trade, and there is no life in society without trade, trade is very important for the evolution of society. An artist must love provocation, he is made to wake up society a little, because what immediately pleases you, and what displeases you remains in history.

How do you see contemporary art?

Right now, it’s diversity, because information teaches you everything at top speed; this artist is known at that time, but if he is skilled, he will be known much faster than before. When I arrived in Paris, a forty-year-old artist was considered a young artist.

Today, we are in a time when there is no major art, everything is equal because the information is massive. It’s a blurry time, we don’t know what will be received the next day. Of course, I guess it is but it is a time when there is no movement, New Realism is the last movement in “ism” and it dates from sixty years ago.

What do you wish for new generations of artists?

Freedom, that’s it! That everyone has the right to do what they want and that there is no ex cathedra authority.

Jacques Villeglé is represented in France by the Galerie Georges-Philippe et Nathalie Vallois, Paris.

Jacques Villeglé – copyright : Photo Michel Lunardelli.

Jacques Villeglé – copyright : Photo Michel Lunardelli.

Camille Bryen et Jacques Villeglé mars-avril 1995, paris « Bonarprte »

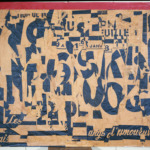

Ach Alma Manetro – février 1949 60 x 260 cm – Affiches lacérées marouflées sur toile – Collection Musée national d’art moderne/Centre de création industrielle, Paris – Photo Anonyme

L’Humour jaune – boulevard Pasteur – février 1953- 93 x 110 cm – Affiches lacérées marouflées sur contreplaqué – Mac, galeries contemporaines des musées de Marseille – Photo Fabienne Villeglé

Boulevard Pasteur – 1956 – 15,5 x 13 cm – Affiches lacérées – Photo Fabienne Villeglé

Boulevard Saint-Martin – août 1959 – 135 x 167 cm – Affiches lacérées marouflées sur toile – particulière, Allemagne – Photo Anonyme

Concarneau – juillet 1995 – 93 x 102 cm -Affiches lacérées marouflées sur toile – Photo François Poivret

Photo de Jacques Villeglé (page “Les interviews”) – copyright : Photo Michel Lunardelli.